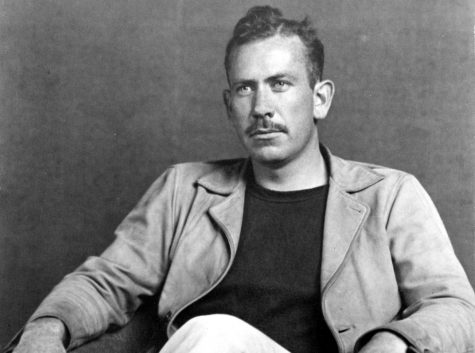

Defending John Steinbeck

March 29, 2019

It’s hard to give people things—I guess it’s harder to be given things, though. Seems silly, doesn’t it?” remarks Lee, a Chinese servant, in John Steinbeck’s multigenerational epic, East of Eden. Lee represents an outsider in the novel, but one who observes and listens intently from above. Lee is only fictional, however, and it is clear Steinbeck is using him to unleash the author’s own vast knowledge and understanding of humanity. When put together, all the characters in the novel become one human, each individual representing some aspect of the mystery of man. It is Steinbeck’s mission to solve this mystery, and he does so through detailed dissection. Lee embodies observation, Adam Trask estrangement, Cathy Ames vice, Sam Hamilton wisdom, Cal Trask jealousy, Aron Trask arrogance, and on and on. The 600 pages begin to forge together into a portrait of man, yet in each page remains a distinct experience of humanity. Any reader who comes across this sensational novel is awestruck by the incredible wisdom of Steinbeck, and one can only set the book down with a satisfied grin of reverence.

Well, not any reader.

I took my copy of East of Eden to work one day to read during my lunch break. When my cubicle neighbor noticed the book, a glare of disgust overcame her expression. I looked at her frightful demeanor and let out an indignant, “What?”

She began to question me, wondering why I wasted even a penny on the “worst book [she’d] ever read.”

I sat in shock, questioning my own judgment, thinking about how many times I had told people that East of Eden was my favorite book because it had changed my entire worldview. But maybe I was mistaken. Who was this joker John Steinbeck anyways? Are his books as great as I think they are?

My co-worker explained to me how she felt about all the excruciating, painstaking details. It turns out she didn’t feel too great about them, as they “add nothing to the plot.” She continued by saying that the book could be about “ye big” (holding her hands closely) instead of “ye big” (spreading her hands unbelievably far apart).

I sunk deep into my chair and further into my shock. I again thought back to the many times I would tell people that the details were what made East of Eden my favorite book. Something was most certainly wrong with my judgment.

She demanded a reason for my ardent love of Steinbeck’s work, but my only rational reason had just been trampled on by her stampede of flagrant insults. So instead of responding, I stayed in my chair, eyes wide, staring into the eyes of my reflection in my smooth coffee mug, questioning those eyes, prodding them for some answers, begging for reasons…

I believe that the things we love most dearly often live outside the realm of rationality. Man has been in search of rational answers since the beginning of time, but man is still searching. What does that tell us?

I cannot give a rational answer to the question of why I love East of Eden. But I know I have learned something from it.

When I read the book for the first time, I surely noticed all the one-liners of wisdom interspersed throughout the chapters. Yet what I thought was Steinbeck explaining things about life was really just Steinbeck observing things about life. He never tells the reader that something is true and something is not. Instead, he tells the reader that something is true, and that another thing at the exact same time is also just as true. Steinbeck paints a picture of life, but he doesn’t embellish or blot out with his brush. He paints what he sees, and leaves any search for meaning up to the thirsty, analytical, rational reader.

East of Eden is one of those books that should never be taught in an English class in school. East of Eden is meant to be read on a sunny day, lounging in an Adirondack chair, feet up, and spirits high.

East of Eden is a great book. Chew it slowly.