By Ben Hebert ’17

One of the main reasons we study history is to learn more about each other. By studying the tendencies and desires and mistakes of other humans, we aim to develop an understanding of the human condition, and an understanding of the features of human interaction that have given rise to conflict in the past. These, of course, are the same human qualities that will lead to conflict in the future. By understanding the variation with which our species has valued things like religion, government, and family, we might be more prepared to enter a world inherently filled with a wide diversity of opinions and morals that have been at odds with each other from the start of time up until the present day. An understanding of human differences throughout history helps us make informed choices regarding our own opinions and morals, which will inevitably affect our lives and, on a larger scale, modify the trajectory of our society. The trouble is that at US, we are only given part of the story. At US, like most schools in the country, the history we learn is overwhelmingly a history of the West. Our K-12 history curriculum revolves Europe and the United States, giving only semester long electives (if even that) to the entire histories of Africa, Asia, and even South America. By ignoring the history of the East, we are neglecting an enormous set of tendencies, conflicts, morals, and opinions that have been and are equally influential upon the human condition as those of the West.

It starts at a young age. As a lifer at US, I can confidently say that the only significant exposure I got to Eastern history and culture was in 4th grade, during our China unit. Only one year out of nine at the Shaker Heights campus can I remember comprehensively studying an Eastern civilization. Because my classmates and I were not adequately exposed to the culture of the East, we were most definitely less likely to become interested in such culture as we became more engaged students in Hunting Vallet.

As eager freshman, we cracked open the Spielvogel textbook, and we were unlikely to notice that our study of history was to be incomplete, or even realize that studying eastern history might have any real value. Granted, as freshmen, we had a little taste of early Chinese and Indian history, but the few weeks allotted for those themes quickly faded into obscurity as we took page after page of notes documenting the rise and fall of Rome, the creation and conquest of European kingdoms, and the shifting landscape of Christianity. We were oblivious to the fact that while all these events took place, rulers and cultures of China and India were developing themselves.

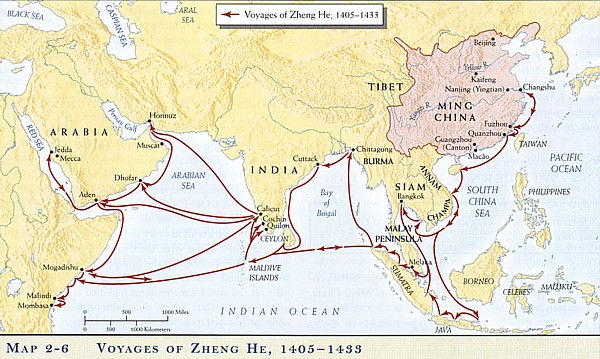

All throughout the great continents of Asia and Africa, great powers were taking thrones, governments were being instituted, religions were shaping people’s lives, great people were doing great things, and bad people were doing bad things. Some might argue that these stories are not as important as those in a Western Civ textbook, because those civilizations were less developed, less advanced, and less influential upon the course of history. I disagree. No matter how advanced Eastern civilization has been throughout its history, it has influenced the human condition to a great degree, maybe even more than the West.

Today, five and a half billion people live in Africa and Asia. That’s most of the people on Earth. The sheer number of people who were born, lived, and died in, say, Cambodia is enough to warrant that country’s existence to be at least mentioned in a history class at US. Though Cambodia might not be known for it’s military might, influential philosophers, or world changing innovations, it would go against the very purpose of studying history in the first place to never talk about it in a classroom. What important events make up Cambodia’s history? I have absolutely no idea, and that’s a problem.

Yes, we do offer a semester long modern China course at US, and a semester course on South Africa too, but that is certainly not enough. We need to change the way history is taught, not simply add an extra elective to take as a second semester senior. US should consider revamping our entire K-12 history curriculum, to make it more inclusive of the often-neglected civilization and culture of the East and South. Maybe instead of Western Civ, we should have a World Civ curriculum for Freshman and Sophomores. Surely US could sprinkle in a little African history into Mrs. Pickwick’s E.S. class, or a little India to that of Mr. Nobbe. In a fast-paced, technology driven world, students today will be brought up into an environment that is far more connected that it has been in the past. Mountain ranges and open waters no longer prevent us from connecting with people on the other side of the globe. To prepare us for this truly global world, US should consider updating its history curriculum.